Welcome to part two of The Beginner’s Guide to Freediving, the best place to start your freediving journey. In this chapter, we take a look at the history of freediving – from it’s ancient history and the birth of modern freediving right through to freediving pioneers and freediving as a sport.

History of Freediving – Introduction

Scientists have begun to believe that we humans spent many millions of years of our evolutionary development living a semi-aquatic existence. Not as a strange, gilled half-man, half-fish creature, but as an aquatic ape. Standing on two legs in the shallows in order to breathe and evade land-bound predators, our hairy forebears used their hands to gather a bounty of easily harvested food, high in protein and omega oils that helped to facilitate brain development. As a theory, the idea of the aquatic ape helps to explain the layer of subcutaneous fat we have under our skin to keep us warm; the way our finger-tips wrinkle after extended time in the water, making it easier to grip things underwater; and, of course, the famous ‘mammalian dive reflex’, which enables us to freedive deeper, safer and longer. Studies have also shown that if trained early enough, our eyes can adapt to seeing underwater, and we know that if babies are immersed in water their eyes open, their epiglottis closes and they can ‘swim’ back up to the surface. We will be exploring the mammalian dive reflex in more depth, pun intended, in a later chapter.

History of Freediving – Ancient History

In terms of our more recent history, we know for a fact that humans have been freediving for food for at least 8,000 years. Archaeologists investigating the mummified remains of the Chinchorian, an ancient peoples that lived circa 6,000BC in what is today Chile, found them to have suffered from exostosis, the condition where the bones of the ear canal start to grow across the opening to help protect the eardrum from repeated exposure to cold water. It’s a condition known in modern parlance as ‘surfers ear’, though divers, surfers and kayakers are equally likely to suffer from it – as is anyone who’s repeatedly dunked underwater. The Chinchorian and their ilk weren’t freediving for pleasure, though, but for food and goods to trade. Pearls and sponges were among the first underwater items to find value amongst in-land societies and those without the skills with which to dive for them. In 332 BC, Alexander the Great famously used freedivers to dismantle the underwater booms preventing his ships from entering the harbour during the siege of Tyre.

History of Freediving – Sponge Divers and The Birth Of Modern Diving

Further research into the history of freediving reveals that in 1913, uniting warfare and commerce, a Greek sponge diver, Stotti Georghios dived to over 60m to locate the missing anchor of the pride of the Italian navy, the Regina Margherita. Stotti was no Greek god, mind; weakened by pulmonary emphysema and half deaf from perforated eardrums, he dived for over three minutes, getting to depth by holding onto a giant rock and tying a rope around his waist so he could be pulled back to the surface. A very primitive form of No Limits freediving, he succeeded retrieving the anchor and was rewarded with the then-princely sum of £5 and lifelong permission to fish with dynamite…

Despite the tale of Stotti Georghios making the headlines, freediving wasn’t a means of recreation in those days, mainly due to the problems of the cold, restricted vision and trouble equalizing. Matters soon changed. In 1927 Jacques O’Marchal invented the first mask designed to enclose the nose and in 1938 Maxime Forjot improved it, using a compressible rubber pouch to cover the nose that enabled divers to pinch shut their nostrils, making it easier to equalize the pressure in their ears.

Another Frenchman, Louis de Corlieu, patented fins in 1933 as ‘swimming propellers’. His design was later modified and mass produced by an American, Owen Churchill. Seeing the potential for their use in wartime, the Britain and the US purchased big quantities during WWII. In 1951 a physics student and diver called Hugh Bradner developed the first wetsuits from neoprene, and again the US Navy snapped them up— this time for use by marines in the Korean war.

1949 was the birth of modern freediving as we know it, when Raimondo Bucher, a Hungarian-born Italian air force captain, dove 30m to the bottom of the sea near Naples on a wager. Scientists confidently predicted he’d die from the crushing pressure at that depth, but he returned to the surface unscathed and 50,000 lire better off.

Over the following two decades freediving exploded in popularity, offering a heady mix of competition, science and derring-do, with the trinity of Bob Croft, Jacques Mayol and Enzo Majorca at center stage.

History of Freediving – The Modern Freediving Pioneers

Exploring more recent events in the history of freediving, in the 1960’s, Bob Croft, a US Navy diving instructor, spent 25 hours a week in a 30m deep tank teaching submariners how to escape from stricken submarines. There he began breath hold training and could soon hold his breath for over six minutes. These amazing abilities got him a job as a guinea pig for Navy scientists looking to discover if the phenomena known as ‘blood shift’, which had been witnessed in diving mammals, could happen in humans. Croft also developed the technique of lung packing, forcing extra air into his lungs prior to a dive or breath hold.

Robert (Bob) Croft is the grandfather of USA Freediving and the first person to hold a freediving world record as a US athlete.

Encouraged by his colleagues, Croft established three depth records over a period of 18 months and in 1967 became the first person to dive beyond 64 meters (the depth scientists believed was the physiological depth limit for freediving). He would go on to reach a depth of 73m in 1968 before retiring from competitive freediving.

Another important pioneer in the history of freediving is Enzo Majorca, an Italian, achieved his first world record in 1960 with a dive to 45m and in 1962 became the first person to break the 50m mark. He continued breaking records until 1974 when, during an attempt to reach 90 meters, he collided with a scuba instructor. Upon re-surfacing, Majorca gave vent to his frustrations with a torrent of foul language – all picked up by the live TV cameras that were present to record his moment of glory. He was subsequently banned for 10 years. His official return to the sport in 1988 was marked by a dive to 101m – his last before retiring. Both his daughters, Patrizia and Rossana, continued to do the Majorca name proud, notching up several world freediving records between them.

The Big Blue, the film by Luc Besson, fictionalized the competitive relationship between Enzo Majorca and Jacques Mayol. Jacques, a Frenchman, was the first person to break the 100m barrier and he also served as a test subject for science, demonstrating that his heartbeat decreased from 60 beats per minute to 27 during that dive. Science had always been playing catch-up when it comes to explaining the incredible feats of freedivers, and the governing body at the time, CMAS, became more and more alarmed at the depths that Mayol and Majorca were descending to, so much so that it decided to stop ratifying records in the early seventies in an attempt to dissuade further attempts. This didn’t stop the record attempts, though, and in 1988 Italian Angela Bandini stunned the world with a 107m dive.

History of Freediving – Freediving As A Sport

The world of competitive freediving lifted many more divers to prominence in the nineties and continues to do so in the present day. We don’t have the room to name them and their incredible achievements here, save for five Tanya Streeter, Umberto Pelizarri, Natalia Molchanova, William Trubridge and Herbert Nitsch.

Tanya Streeter began breaking records almost immediately when she began freediving in her mid-twenties and in 1998 reached 113m with a No Limits dive. A fearless competitor, she twice held records that were deeper than the men’s equivalent: a No Limits dive to 160m in 2003 that has never been broken, and a record Variable Weight dive to 122m that was held for seven years.

Also setting the freediving world alight in the 90s was the Italian Umberto Pelizzari, achieving records in Constant Weight, Variable Weight and No Limits freediving. He founded the freediving agency Apnea Academy, wrote a manual of freediving, and today teaches and works as a TV host and university professor.

William Trubridge, a double world record holder, has the distinction of being the first person to dive to 100m in the discipline of Constant Weight without fins. (Until 2003 it wasn’t even considered possible to achieve that depth without the aid of fins.)

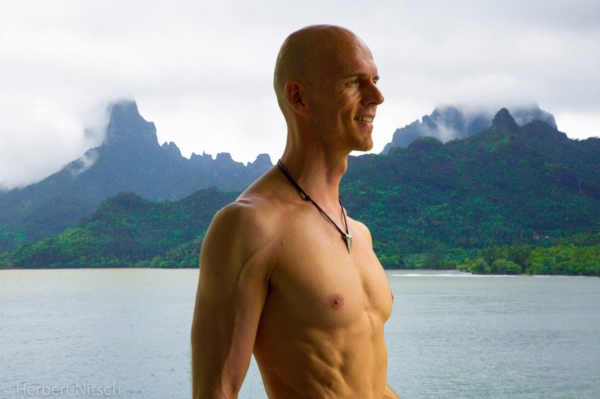

Herbert Nitsch is an Austrian freediver who has held 32 world records across every freediving discipline. He is the current No Limits world record holder after descending to 214m – a depth that is unlikely to be beaten for many years due to the extreme difficulty and risks involved.

As you can see, the standard of competitive freediving rises each year, along with the number of recreational freedivers attracted to such a wonderful sport. The history of freediving is as fascinating and attractive as the discipline itself. Nowadays there are many agencies providing high-quality freediving courses and tuition – something that could never have been imagined even ten years ago.

Written by Emma Farrell

The Beginner’s Guide to Freediving is written by Emma Farrell. She is one of the world’s leading freediving instructors and has been teaching freediving since 2003. She is the author of the book ‘One Breath, a Reflection on Freediving’, has written courses that are taught worldwide, taught gold medal winning Olympic and Paralympic athletes, and has appeared numerous times on television teaching everyone from Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall to Ellie Simmonds how to freedive.

Learn to freedive with the author of The Beginner’s Guide to Freediving

Go Freediving is the longest established, most experienced and friendliest freediving course provider in the UK, led by world class freediving instructor trainer Emma Farrell, and her team of personally trained instructors. No other course provider has such a good instructor to student ratio, safety record and personal touch.

Whether you’re a beginner dipping your toes into the world of freediving, a seasoned pro looking to turn professional, or simply a freediver of any level who wants the best freediving holiday in the world, we’re here for you!

Learn more about Freediving

Read the previous chapter of The Beginner’s Guide to Freediving – ‘What is Freediving?’ here now

Read the next chapter of The Beginner’s Guide to Freediving – ‘Glossary and Acronyms of Freediving’. here now

Want more from Go Freediving?

Scroll to the bottom of our webpage where you can sign up to our newsletter, find the dates for all upcoming trips and courses, read even more blogs, or connect with us on social media!

See you in the water!

This article first appeared on Deeper Blue.com

Leave A Comment